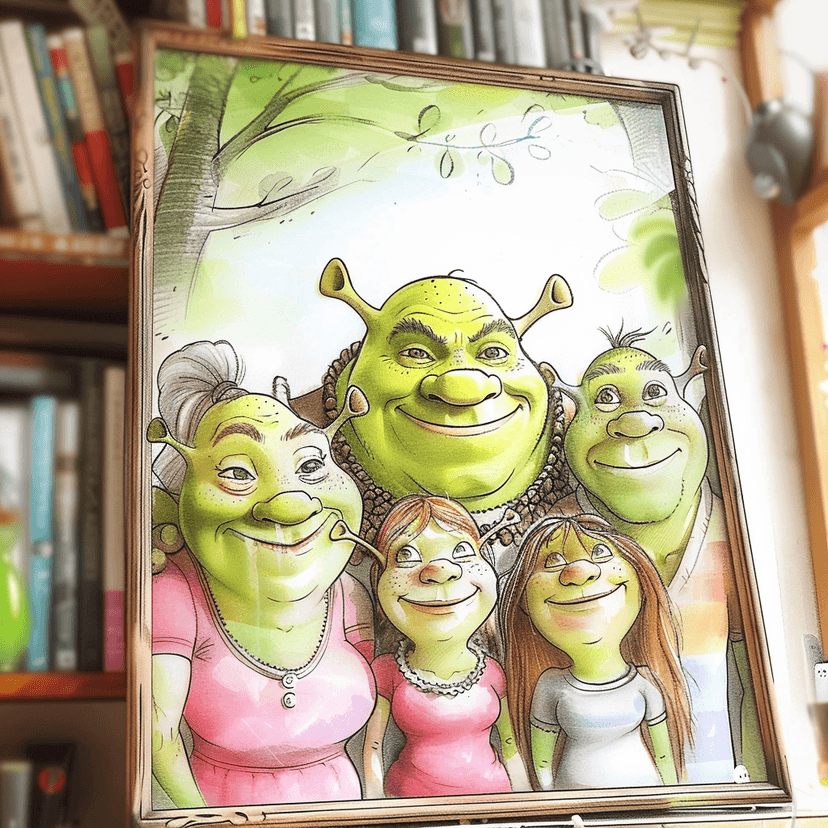

Imagine that you’re a method actor and you’ve just been hired to join the touring Broadway company of Shrek in the titular role. Every night for years you perform as Shrek to audiences across the country, living and breathing Shrek. Then one day, the tour ends and you are no longer Shrek, you go back to your smaller roles in various plays and musicals, but the trouble is you’ve been living Shrek for a long time. Your reputation precedes you, and people have a hard time thinking of you as anyone other than Shrek. Worse, you’ve internalized a lot of Shrek - at this point it’s second nature, the lumbering around, the accent, the affectations. Crossing paths with old cast members can sometimes mean extra effort to not slip back into your Shrek headspace. It’s easy to be Shrek because you’ve practiced so much, but you’re not Shrek, you’re just an actor.

Sometimes I can feel Shrek creep up inside of me when I’m with people who knew me before I transitioned. This past weekend my parents came to visit for the first time in many years. We had a phone call recently where I told them that prioritizing visiting me would make me feel supported in my transition, and they did just that. The last time they saw me in person was when I was eight months in, and I probably seemed like a very happy mess. I’m still happy, but I have so much better of a grasp on who I am now, and I’m more practiced at feeling my feelings and being present in my body. Still, because they knew me as Shrek for so long I felt anxiety about whether they were seeing past my green days. I couldn’t shake the feeling that I wasn’t being enough not-Shrek. Although they were referring to me as their daughter, I felt like a woman who was their son, and I worried that I wouldn’t seem “different enough” from Shrek for them.

One helpful reminder a friend gave me after the visit was that just because I had ways of connecting with my parents before transition didn’t necessarily make them Shrek things. I enjoyed spending our time together nerding out with my dad about oldies music, and exchanging deep thoughts with my mom about the state of the world. Those things aren’t gendered, and it’s where we know we can always find common ground. Still, I wasn’t sure what in my eyes would make me feel more like a daughter around them.

But what does it mean to feel like a son, anyway? Like I’ve written about before, I didn’t grow up as a boy, I grew up as a closeted trans girl. My parents and I had so many interactions where I think a cis son would have responded to things in a way I did not; I was “socialized trans” and they had to internalize that in their parenting. I think I’m expecting them to treat me differently because I’m still struggling to shake my own self-perception as Shrek in the time before my self acceptance. Even now, more than two years in, I have to remind myself that I was never really Shrek. There are some behaviors that my parents would have changed when I was young had they known I was their daughter and not Shrek, but also in many ways they always treated me as their trans daughter whether they knew it or not.

If I’m honest, the truth is talk has always been cheap with my parents. In my childhood there were so many speculated career shifts, moves to other locales, potential pets and adopted siblings that never came to fruition. Additionally, Baby Boomers aren’t exactly known for their emotional vulnerability. Before the trip, my mother ran an estate sale to purge my late grandmother’s house of valuables. When she arrived in Portland, she gave me a delicate champagne pearl necklace that had been in the family since at least the 1950s, a treasure she had saved me from my grandmother’s jewelry box. I think I need to give more credence to my parents’ actions, and consider that they might be trying to treat me as their daughter as best as they can. Pearls are not exactly the kind of present that you give to an ogre.